Forced Neighborhood

Kösk, Munich, germany

May, 2023

We do not choose our neighbours, rather we seek to get along with them in order to develop or maintain a respectful, if things go well, trusting, and even better, a friendly relationship. If the relationship is with neighbouring nations, these relationship gradings also apply, but extended to include trade and exchange, for example in the areas of language and culture. Large, economically strong neighbouring countries have a regional responsibility, which they fulfil or fulfil in different ways and to which the neighbouring countries must respond. History shows many examples of "inharmonious neighbourly relations" which, due to imperial expansionism, led (or led) to border conflicts and even wars of aggression and, beyond that, to colonialism. The consequences and the accompanying suffering of death, injury, deprivation through flight, expulsion and oppression of the people affected continue. In 20th century Europe, it was precisely from German soil that unprecedented misfortune emanated over its nearest and farthest neighbouring countries, but also within society this behaviour of criminal National Socialism, aimed at the subjugation and destruction of other nations and their populations, culminated in the breach of civilisation through the systematic murder of supposed "enemies of the people" in the Shoah. Against this background, the fact that today we can experience a surprisingly stable, trusting and responsible cooperation with the European Union cannot be appreciated highly enough; the preservation, expansion and deepening of this association of democratic states constantly requires the joint efforts of all its members, i.e. citizens, in order to continue.

The will to take responsibility, rather the hegemonic aspirations of the former Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, or USSR for short, could/would do little to counteract its neighbours and neighbouring neighbours. Regardless of the historical perspective of the formation of blocs in East and West, the "big brother," as the USSR was metaphorically and, in my view, euphemistically called in the German Democratic Republic, exerted ideological, economic, military, but also cultural pressure on its sphere of influence of 15 Soviet republics and seven states of the Warsaw Pact. Its cultural doctrine of a supposed soft power permeated the lives of its many "neighbours" as propaganda, at least in the official environment, even if the varieties may have shown regional differences. Thus, it can be simplified to say that under Russian-style socialism, people from the Baltic to the Bering Sea were confronted not only with a unified ideology, but also with the aesthetic conception that went along with it, the reverberations of which have lasted into post-Soviet times. In the visual arts, from 1932 onward, enacted Socialist Realism replaced any avant-garde aspirations that had developed since the upsurge in cultural production following the October Revolution of 1917. As mass art, "Socialism" transported motifs of strong realism without critical aspects: the laboring man working united for the goal of a communist society; whitewashing production conditions in factories and idyllizing the collective farms, military power symbolism on land, water as well as air (and then the outerouter space), and scientific exaggeration on panels, posters, mosaics and frescoes to permanently illustrate this claim to sovereignty.

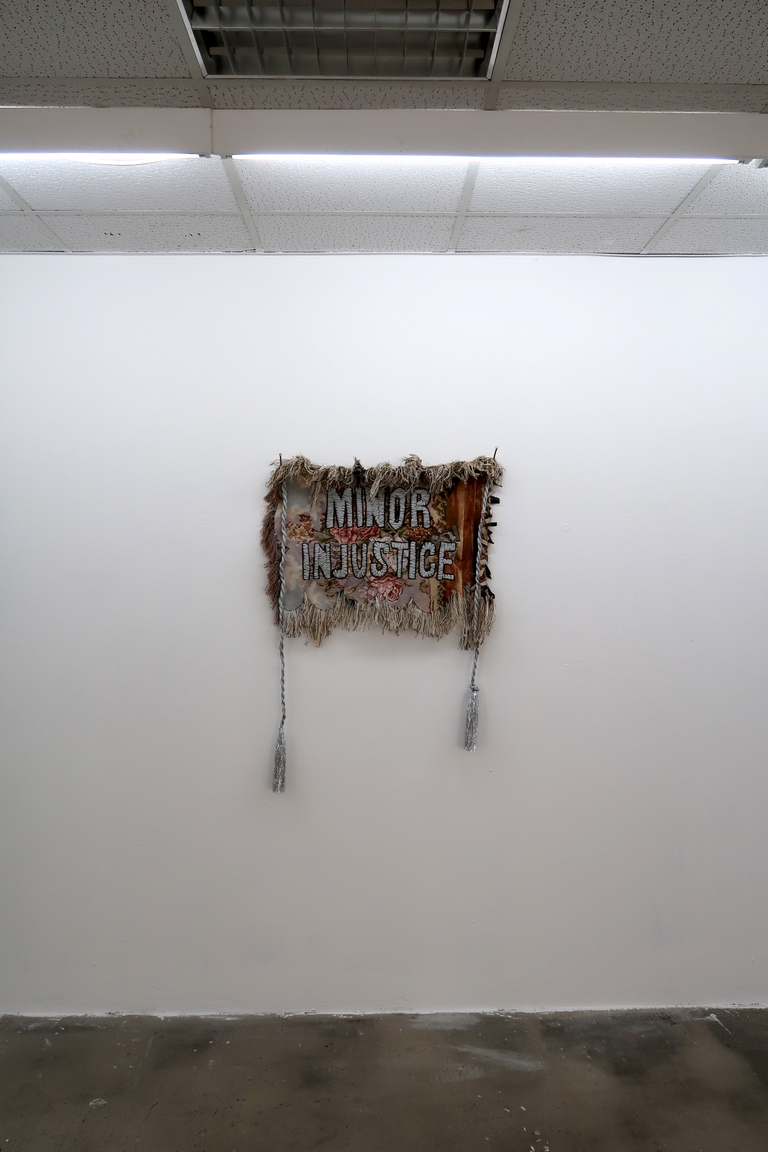

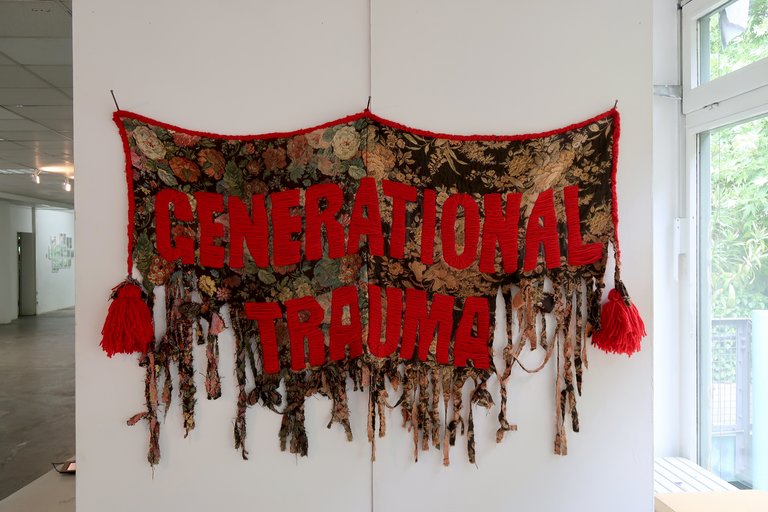

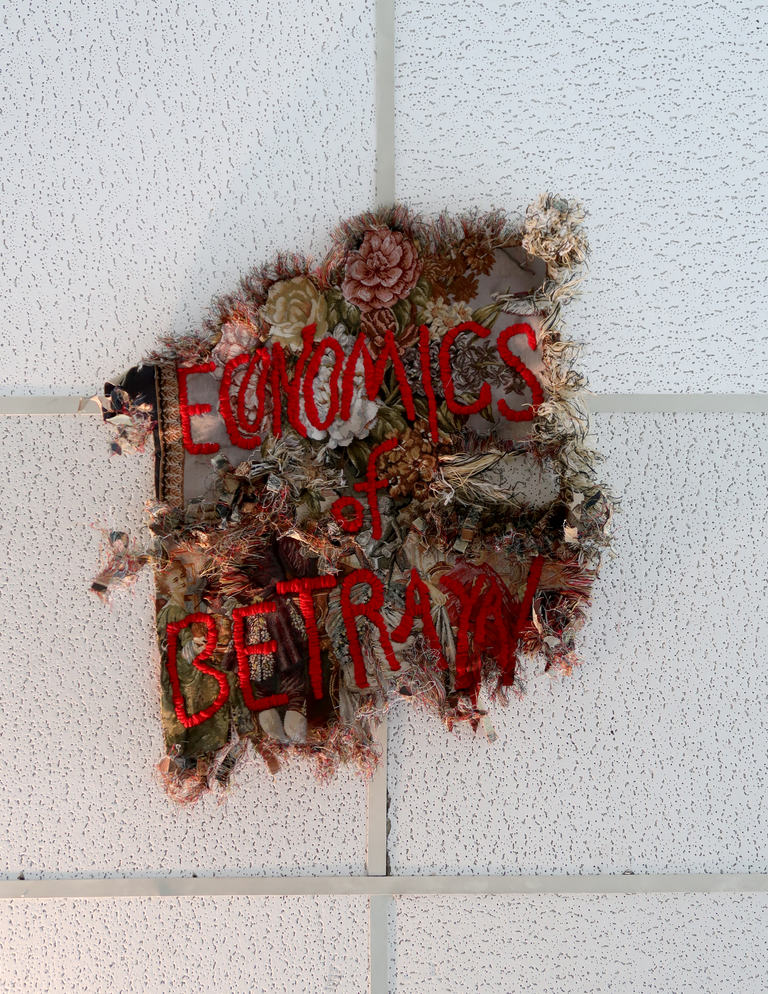

The biographical roots of the three artists Gvantsa Jishkariani, Xenia Fumbarev and Michael Grudziecki lie in the post-Soviet sphere of influence of Georgia, Ukraine and Poland. Despite different approaches to their work, ranging from painting, drawing, and printmaking to sculpture, objects, new media, and perfomance, the three positions are united in one area of their aesthetic approach and engagement by their encounter with a "socialist visual world." Michael Grudzieski, who travels and documents his environmental experiences in paintings, has won over his two colleagues Gvantsa and Xenia for this exhibition project, and we viewers can approach them, among other aspects of their works, also and before the perspective of a forced neighbourhood.

Personal digression: Before we approach, however, I try the understandable Anglicism "(there is) an elephant in the room", a rabid bear rather. It must be stated: The former "big brother", today's Russian Federation, the largest country on earth in terms of area, is preparing to forcefully shift and expand its borders by trying to destroy its neighbouring country Ukraine through its invasion in violation of international law with unleashed ruthlessness and contempt for humanity. Close European neighbours, but also more distant partner nations, which have been brought closer by globalisation, are trying to support Ukraine in its defense against the aggressor Putin and the forces serving him. Poland is providing special help in this regard, not least by taking in many refugees. But Russia's neighbour Georgia also faces a permanent threat, and not just since the Caucasian Five-Day War of 2008. The "forced neighbourhood" has become a life-threatening neighbourhood that affects us all. End of digression.

Text by Alexander Steig

Photos: Michael Grudziecki